192. Berlin Historical Museum at the Berlin Fair

Berlin, It’s Just Not Fair!

Berlin (Google Maps location)

October 3, 2010

Remember way back when… Back when my hair was mostly still dark and Damian was not yet even 18 months old? Back when silly ol’ me thought there were only a few hundred museums in Connecticut and there we were, young and spry, visiting the 9th museum for this project? Of course you do. But just as a reminder, here it is, our visit to the Berlin Historical Society Museum in May of 2007. Those were simpler times to be sure.

Remember way back when… Back when my hair was mostly still dark and Damian was not yet even 18 months old? Back when silly ol’ me thought there were only a few hundred museums in Connecticut and there we were, young and spry, visiting the 9th museum for this project? Of course you do. But just as a reminder, here it is, our visit to the Berlin Historical Society Museum in May of 2007. Those were simpler times to be sure.

Three and a half years later, the three of us had a sort of “replay” of that fine spring day at the museum’s annual incarnation at the Berlin Fair. (And it’s actually almost FIVE years later that I’m getting around to writing this page.) So, is this the same museum, just moved across town? Am I padding my numbers? To both questions, I answer absolute no’s. (Really? Do I really have to pad my numbers? That’s ridiculous.)

The historical society’s efforts at the fair are quite similar to their more permanent museum, but it’s a different museum. I swear. For one, it’s in a barn. See, there you go.

I have never been a fan of these town fair things that are so prevalent in New England. (We simply didn’t have them where I grew up; all we had were ethnic fair – Greek and Italian was all – and my dad never let us go to them probably because they were raising money through games of chance for those terrible Catholics and Greek Orthodox. I’m only half kidding.) Anyway, I became a bigger fan of our fairs when I started learning that several of them have museums within their confines. A couple, like Berlin, actually have more than one museum! So even though I don’t like crowds or friend food or carnies or tractor pulls or weird vegetable contests, I am now excited to go to the fairs with museums.

I have never been a fan of these town fair things that are so prevalent in New England. (We simply didn’t have them where I grew up; all we had were ethnic fair – Greek and Italian was all – and my dad never let us go to them probably because they were raising money through games of chance for those terrible Catholics and Greek Orthodox. I’m only half kidding.) Anyway, I became a bigger fan of our fairs when I started learning that several of them have museums within their confines. A couple, like Berlin, actually have more than one museum! So even though I don’t like crowds or friend food or carnies or tractor pulls or weird vegetable contests, I am now excited to go to the fairs with museums.

And that’s how we got here. (My page on the Berlin Fair). From their own history: “From its inception in 1882 as a Harvest Festival, The Berlin Fair still remains a focal point of the community. In the early 1900’s, the festival became the State Agricultural Fair and was held annually until 1919. It was later brought back to life in 1948 by The Berlin Lions Club. It is always held the first weekend of October and it’s no different from any other of Connecticut’s larger town fairs – except that this one has the Berlin Historical Museum!

Since I never forget anything I ever see at any museum ,em>ever, I was curious what this Open-only-3-days-per-year version had for me. For one, it had several different exhibits and a functional and “countrified” theater of sorts which was playing some video about Berlin’s history. Or maybe it was an episode of “Hee-Haw,” I never really noticed. When you’re Berlin, you play up two things: Tin, steel and brick.

Since I never forget anything I ever see at any museum ,em>ever, I was curious what this Open-only-3-days-per-year version had for me. For one, it had several different exhibits and a functional and “countrified” theater of sorts which was playing some video about Berlin’s history. Or maybe it was an episode of “Hee-Haw,” I never really noticed. When you’re Berlin, you play up two things: Tin, steel and brick.

No, Berlin is not our most exciting town. But in reality, these three products made people in this town very rich and somewhat “famous” (as these things go.)

One corner of the museum was set up to be “Pattison’s Tin Shop,” which as we learned all those museums ago, was referencing Irish brothers and tinsmiths, Edward and William Pattison. The two were the first to begin tinsmithing in the colonies and sold their wares door-to-door in town out of the back of a little wagon. They were to original Yankee Peddlers. Or so Berlin claims: “They set up the first tinware business in the colonies. Wares in baskets were pedaled from house to house, then as surplus accumulated, by mule and wagon, traveling all over America and to Canada. This was the birth of “The Yankee Peddler”.”

That’s Vietnamese for “overjoyed” face

Good enough for me. I should also mention that the Berlin town seal is a drawing of a Yankee Peddler. The fair’s museum had a nice collection of tin products and a how-to of how tin is made. The dots were connected from the fading tin industry to the growing steel industry. While Berlin may not be remembered for steel, per se, it certainly is known for its bridges. Specifically, the Berling Iron Bridge Company.

The great PAST website says:

“The firm of Roys and Wilcox, an East Berlin maker of tinners’ tools and other metal-forming mechanisms, set up a separate company in 1868 to market sheet-iron products made with its rolling machines. The Corrugated Metal Company, as it became known, produced roofing material and metal-clad firedoors and shutters. The company soon became involved in structural ironwork when it began to provide roof trusses as well as the exterior material. The enterprise was not particularly successful until a new investor in 1877, S. C. Wilcox, realized that the plant had the capacity to manufacture highway bridges. The following year, the Corrugated Metal Company purchased rights to William Douglas’s patented “parabolic” truss and produced the first of the lenticular bridges that would soon dot the landscape of the Northeast. Douglas, educated at West Point, joined the company as treasurer and executive manager and continued to refine his design; he was awarded a second patent in 1885, by which time the company had changed its name to the Berlin Iron Bridge Company.

The late 19th century was a good time to be in the iron bridge business. As the industry developed, the price of iron trusses steadily dropped until they were competitive with wooden spans, especially when their superior durability and resistance to damage during floods was figured in (wooden bridges typically lasted only 20 to 30 years). The only other alternative, for shorter spans only, was building arches in stone, which remained very expensive. Throughout America, local highway officials opted to replace their wooden bridges with iron, and firms such as the Berlin Iron Bridge Company were happy to oblige.

At its height, the Berlin Iron Bridge Company was probably the largest structural fabricator in New

England. Some 400 workers were employed at its East Berlin plant, with another large group of workers in the field during the construction season. There is no definitive count of the company’s bridges, though at least 600 are known to have been completed during its first ten years, and the company itself claimed at least 1,000. Most were in the Northeast, though even today Berlin trusses survive as far away as Texas. A few multiple-span bridges were of tremendous size, but most were a single span in length, with through-trusses used in crossings over 100 feet and pony trusses for shorter spans. The lenticular design accounted for the bulk of the company’s output, although it also produced other bridge types, specialized industrial structures such as dock cranes, and ironwork for roofs and buildings.

The Berlin Iron Bridge Company was absorbed in 1900 by the American Bridge Company, a largely successful attempt by J.P. Morgan to monopolize the country’s structural fabricating industry. Almost immediately, some former Berlin Iron Bridge employees started a new firm, the Berlin Construction Company, which soon regained much of its predecessor’s influence in the New England bridge market. It remains in business today as Berlin Steel.

Phew. That was a lot. I think I wrote a lot about the Berlin brick industry over on the “real” museum’s write up so I won’t go so crazy here. But I did learn at the fair museum that those ponds along route 9 down near where the Showcase Cinemas lot is? Those aren’t natural lakes at all, but rather the pits left over from clay mining for bricks back in the day. Now we know. You should also know that Berlin bricks were the best bricks you could brickin’ buy back in the day. If you are a normal person, like me, you’d be amazed how many people have come to that other Berlin History Museum page looking for information on collecting bricks. That page is linked from several brick collector websites. Why you would want to collect bricks is beyond me… Actually, collecting anything is beyond me, but that’s not what we’re here to talk about.

Phew. That was a lot. I think I wrote a lot about the Berlin brick industry over on the “real” museum’s write up so I won’t go so crazy here. But I did learn at the fair museum that those ponds along route 9 down near where the Showcase Cinemas lot is? Those aren’t natural lakes at all, but rather the pits left over from clay mining for bricks back in the day. Now we know. You should also know that Berlin bricks were the best bricks you could brickin’ buy back in the day. If you are a normal person, like me, you’d be amazed how many people have come to that other Berlin History Museum page looking for information on collecting bricks. That page is linked from several brick collector websites. Why you would want to collect bricks is beyond me… Actually, collecting anything is beyond me, but that’s not what we’re here to talk about.

Unfortunately, there’s really not anything much more to talk about anyway, as this museum is set up for three days every year probably just as an effort to attract attention to the town’s historic efforts. There was a constant flow of people into the museum during my visit and the exhibits were set up really  well. Sure there was the random stuff like an old refrigerator and a “replica stone” marking the 11 miles from the original Berlin post office to Hartford – which, incidentally, was one of the first 75 set up by the first Postmaster General in the country. That first Postmaster General? Yup, Ben Franklin. (And, the original still stands in town, if you want to go see it).

well. Sure there was the random stuff like an old refrigerator and a “replica stone” marking the 11 miles from the original Berlin post office to Hartford – which, incidentally, was one of the first 75 set up by the first Postmaster General in the country. That first Postmaster General? Yup, Ben Franklin. (And, the original still stands in town, if you want to go see it).

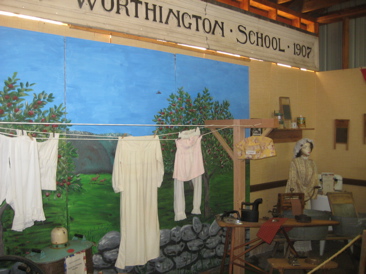

This version of the museum offered a pocketful of brochures. Amazingly, I found my stash in 10 seconds and they are really well written and pretty interesting to read. “Brick Industry in Berlin, CT,” “Berlin, CT Agriculture: Dairy Farms, Cider Mills & The Berlin Fair,” “Berlin, CT Mills,” “Berlin Iron Bridge Company,” and totally random page explaining how much of a pain in the butt washing clothes in the 18th century was.

The most interesting thing I learned from reading all of these just now in the bathroo—err, in the breakroom – was that Simeon North was from Berlin and grew his innovative business here. I’ve learned about Mr. North in museum in Manchester, museums in New Britain, Middletown, Hartford and Bristol. But for some reason, I don’t recall ever reading that he did his thing here, in Berlin. “North was born in Berlin into a prosperous family able to provide all six sons with farms of their own. North was given a farm in Berlin…” says Wikipedia.

There was a crazy convergence of clockmakers and tool makers and Simeon North. A process was invented to make interchangeable gun parts and to this day, North is credited with the invention of the milling machine, the first entirely new type of machine invented in America and one which, by replacing filing, made the production of interchangeable parts practicable. Of course you knew that about him though. Sorry to patronize you.

There was a crazy convergence of clockmakers and tool makers and Simeon North. A process was invented to make interchangeable gun parts and to this day, North is credited with the invention of the milling machine, the first entirely new type of machine invented in America and one which, by replacing filing, made the production of interchangeable parts practicable. Of course you knew that about him though. Sorry to patronize you.

Anyway, North got huge contracts from the government for guns, the production of which he went on to perfect and develop until his death.

Another Berlin inventor I just learned about was one James Lamb. Lamb invented a new kind of stove that became pretty much indispensable in every modernized house. This stove was made on much the same principle as those of the present day, and it was the first one patented in this country in which the heat passed around the oven. A stove was in use before this, but it was a simple box affair.

After getting lost in some story about Berlin bricks at the museum, I turned around to realize my wife and child were gone. While they did indulge me enough to allow for me to read most everything worth reading here, I accepted that it was time to leave and headed back out into the crowds at the Berlin Fair to find my family… Just in time to gather ourselves before the next museum, a mere 200 yards away!

…………………………………………………….

Cost: 12 and up, $12 as of 2011. (seniors are cheaper)

Hours: First weekend in October, fair hours

Food & Drink? Whatever you want. I had a beer and a giant turkey leg

Children? Yes

You’ll like it if: Honestly, you didn’t go to the fair for this

You won’t like it if: you’re some whiney teenager just wanting to ride rides by your dad forced you to learn about tin

Freebies: none

For the Curious:

The Berlin Fair

Berlin Fair program covers

My separate page on the Berlin Fair

Museum 193. The other one at the fair

I’ve observed similar versions of “overjoyed” when I’ve dragged the family along on my adventures. They’re generally good sports but they’ll never truly understand, right?

Comment #1 on 04.06.12 at 7:11 am