AT in CT Section 1

I’m going to write these pages a little bit different from my usual hiking stuff – as if I “thru-hiked” Connecticut even though the pictures clearly tell a different story. Also, I’m not going to bore you with the logistics of how one hikes the whole AT in CT over the course of many seasons and sometimes only with a a couple hours to spare. Bottom line is I’ll be hiking it twice, as I have only myself and my car. But, lucky for you all, that means I get to notice all the stuff all the AT books skip about Connecticut’s oft overlooked little 52 miles.

Section 1

Hoyt Road to Route 341, 11.5 miles

November 2011 and May 2012

Quick – what town do northbound AT hikers enter when they first encounter Connecticut? I’ll give you a second.

Quick – what town do northbound AT hikers enter when they first encounter Connecticut? I’ll give you a second.

What’s your answer?

Most likely, you’re wrong. The AT enters the Nutmeg State in Sherman. Sherman! I must admit that I don’t know much about Sherman. There is a small winery there (CTMQ Visit here) and a little town history museum or two, but their real claim to fame should be the Appalachian Trail. Truthfully, the short section in Sherman really isn’t all that exciting – but Sherman does play an integral role in the formation of the AT in Connecticut.

And fortunately, that role is commemorated by a sturdy iron bridge over the Tenmile River on your way to (or from) Kent – the town most of you probably answered above. More on that brige in a few minutes.

Mile 0.0

Conveniently, for state completers, the AT initially enters Connecticut right at a road crossing in Sherman – Hoyt Road to be exact. I wrote “initially” because the trail leaves Connecticut a few miles north to venture back into New York for a mile or so before re-entering our state on its journey north to Massachusetts. While the AT does waggle along the TN/NC border, popping in and out of each state, I don’t really recall any singular exit/re-entry like we have anywhere along the trail.

There is a little hiker’s lot at the Hoyt Road crossing which is also a nice convenience. I was hiking this section a mere 11 days after the Apocalyptical hellstorm of 2011. Up in my neck of the woods in north-central CT, we lost power for 8 days and every third tree came crashing down under the weight of the snow on the still-foliated trees. There was some damage down here, but nowhere near what we saw in the West Hartford area. Thank goodness, because otherwise I wouldn’t have been hiking.

There is a little hiker’s lot at the Hoyt Road crossing which is also a nice convenience. I was hiking this section a mere 11 days after the Apocalyptical hellstorm of 2011. Up in my neck of the woods in north-central CT, we lost power for 8 days and every third tree came crashing down under the weight of the snow on the still-foliated trees. There was some damage down here, but nowhere near what we saw in the West Hartford area. Thank goodness, because otherwise I wouldn’t have been hiking.

The first flat half-mile passes another hiker’s lot off of route 55 – this lot is positively huge and is right off the trail. Just north of this lot there’s a box containing decent maps of the AT in CT. The box was well-stocked. After crossing route 55, the trail climbs Tenmile Hill which tops out at just over 1000 feet, and then promptly descends down towards the Housatonic.

Ah, the Housatonic… Although this is just a short taste of the river (before ascending again west), we’ll get used to it by our side for a lot more of the hike through Connecticut. As such, we should learn some completely random facts about it. No, not the typical stuff like where it begins (up in the Berkshires somewhere) or how it’s still contaminated by PCB’s from an old GE plant in Pittsfield, MA… No, I’ll give  you stuff like how the river’s name comes from the Mohican phrase “usi-a-di-en-uk”, translated as “beyond the mountain place”.

you stuff like how the river’s name comes from the Mohican phrase “usi-a-di-en-uk”, translated as “beyond the mountain place”.

Better yet, the name “Housatonic” is commemorated by two distinct military happenings. Did you know that every nuclear device test had a name? I didn’t. And I certainly didn’t know that Housatonic was the name given to the very last US air dropped nuclear device (test or otherwise) on October 30, 1962 at Johnston Atoll. (I have stories about the far-flung Johnston Atoll too – and at the risk of getting too far off track, I have to tell one. At my old job working with insurance, we received a note from a guy working with a private military contractor cleaning the remote island up of all its radioactive and chemical agent waste. He was questioning some insurance issues related to having his leg bitten off by a shark. So really, when you complain about your job, at least you’re not cleaning up deadly waste a million miles from civilization while getting your limbs eaten by sharks.)

Going back a little further in time, to the Civil War, The USS Housatonic has the distinction of being the first ship in history to be sunk by a submarine – the confederate vessel CSS H.L. Hunley. Seriously. Hm. Is this why no one wants to hike with me? Because I drop this stuff on them as we go?

And I’ve only just begun…

Mile 2.8

There is a relatively new shelter just off the AT at Tenmile River. It’s a nice one that is situated at the top of a slight rise at the top end of a large field. If you stay here, just remember that the Tenmile water is not potable and that there will be deer in the field when you wake up with the sun in your eyes. There are also no fires allowed along the AT in CT at all. None. Ever.

AT shelters almost universally contain trail registers for hikers to sign in and write whatever they choose to write about. For thru-hikers, these are the best way to “chat” with hikers who are literally following in your footsteps. Tips about trail angels, running springs and future meet-ups are the cell-phones of the trail.

AT shelters almost universally contain trail registers for hikers to sign in and write whatever they choose to write about. For thru-hikers, these are the best way to “chat” with hikers who are literally following in your footsteps. Tips about trail angels, running springs and future meet-ups are the cell-phones of the trail.

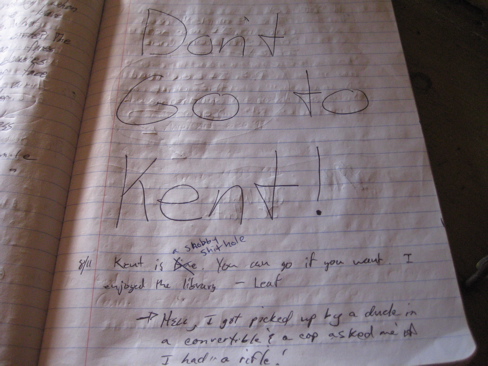

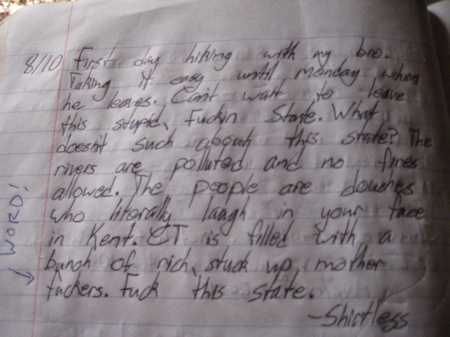

The register at Tenmile contained many rants about nearby Kent, often pointed to as a “Trail town.” Trail towns are those towns very close to the trail that are sizeable enough to contain all the things a thru-hiker needs: A decent sized post office, resupply points and possibly a cheap motel to recharge. Kent is almost universally reviled as the worst trail town from Georgia to Maine.

Now, I happen to love Kent but I also completely sympathize and agree with the thru-hiker logic. (Remember, I was one once.) For one thing, getting picked up by locals for a quick ride to town is nearly impossible in Connecticut. Down south, you don’t even have to stick your thumb out half the time. Here, you have to be a really hot topless woman in Daisy Dukes to get a look. And since those don’t exist on the AT, good luck.

Once in town, Kent is the most expensive town on the whole trail. (Salisbury, CT is a close second, but it’s much more hiker friendly.) There are no cheap grocery stores here and no cheap motels. Heck, the first business a hiker reaches coming up 341 into town is Belgique and thru-hikers aren’t too keen on spending 20 bucks on an ice cream cone, a few pieces of chocolate and a coffee.

Thru-hikers are also notoriously stinky and unkempt. It’s just a fact. It’s also a fact that Kent’s citizenry does not look kindly upon stinky and unkempt people. Sorry, they don’t. So the sentiment about Kent in the logbooks (and online… and in guidebooks) is valid when viewed through the lens of a thru-hiker. For my part, I like to go out to western CT on mid summer weekends looking to help out thru-hikers here and there (that’s what a trail angel is, by the way). No, I won’t change perceptions, but I can feel good trying.

……………………………………………………………………………………………….

Just past the shelter (there’s an outhouse and campground here too) is the Ned Anderson Memorial Bridge across the Tenmile at its confluence with the Housatonic. Which brings us back to Sherman’s role in the early days of the AT. Or, more specifically, deceased Sherman resident Ned Anderson.

Just past the shelter (there’s an outhouse and campground here too) is the Ned Anderson Memorial Bridge across the Tenmile at its confluence with the Housatonic. Which brings us back to Sherman’s role in the early days of the AT. Or, more specifically, deceased Sherman resident Ned Anderson.

Ned was the man. I’m very happy to report that the Sherman Historical Society wrote a nice biography about him and I look forward to buying it from them someday soon. Nestell Kipp “Ned” Anderson (1885–1967) was an American farmer who spearheaded Connecticut’s leg of the Appalachian Trail. In addition to creating and maintaining other area trails for the Connecticut Forest & Park’s (CFPA) Blue-Blazed Trail System, he also organized Sherman’s first Boy Scout troop in 1931, as well as the Housatonic Trail Club in 1932, for amateur and avid hikers.

For hiker historians like me, Anderson is a bit of a hero. I love finding old maps – especially old trail maps – to see the changes over time to some of my favorite hiking areas.

Here’s some good stuff from Wikipedia:

While hiking in 1929, Ned Anderson met Judge Arthur Perkins, a member of CFPA’s Connecticut’s Blue Blazed Trails Committee, who introduced Anderson to Myron Avery. These two men were drumming up interest in Benton MacKaye’s vision of a 2,000-mile contiguous footpath from Maine to Georgia—The Appalachian Trail. Most people with whom they met were interested but few were committing to it; Anderson took an immediate interest.

While hiking in 1929, Ned Anderson met Judge Arthur Perkins, a member of CFPA’s Connecticut’s Blue Blazed Trails Committee, who introduced Anderson to Myron Avery. These two men were drumming up interest in Benton MacKaye’s vision of a 2,000-mile contiguous footpath from Maine to Georgia—The Appalachian Trail. Most people with whom they met were interested but few were committing to it; Anderson took an immediate interest.

Taking on dual roles as Chairman of CFPA’s Blue Blazed Trails’ Housatonic Section in 1932, and as a member of the Appalachian Trail Conference’s Board of Managers (he was the ATC’s 49th member), Ned mapped and cleared, cut, hacked, and blazed the state’s trail from Dog Tail Corners in Webatuck, NY, (coming from Bear Mountain across the Hudson River) which borders Kent, CT, at Ashley Falls, all the way up to another Bear Mountain at the Massachusetts border. Anderson spearheaded and maintained the Candlewood Mountain, Schaghticoke (SCAT-uh-coke) and Housatonic Range trails as well.

Anderson drew the first official maps for the statewide Blue Blazed Trail System, which were made available to hikers in individual booklets.

Anderson drew the first official maps for the statewide Blue Blazed Trail System, which were made available to hikers in individual booklets.

The entire Appalachian Trail was completed in 1937 and by 1939 the National Park Service and U.S. Forest Service were working to formalize and protect the trail as a “scenic trailway.”

Anderson officially retired from trail management in 1948 at age 63, whereupon the ATC board passed a formal resolution expressing their gratitude and sincere appreciation for his labors and accomplishments and distinguished service on behalf of the Appalachian Trail.

……………………………………………………………………………………………….

The 120 foot Ned Anderson bridge is really nice and ushers hikers onto a stretch of about ¾ of a mile along the river amongst a beautiful stand of white and red pine.

Mile 4.1

The trail crosses Bull’s Bridge Road at the Schaghticoke Road intersection. From here, you can walk the short distance down to one of Connecticut’s few remaining covered bridges – Bulls Bridge. There’s also a huge parking lot across the river here too. I think the bridge is kind of ugly, but it’s still a worthy side trip and will make you appreciate the West Cornwall Bridge up the trail just that much more.

Here’s my page about Bull’s Bridge.

After trudging down Schaghticoke Road for a while, the AT turns west and heads up Schaghticoke Mountain. Now, the Schaghticokes… Like many native American groups, their long and proud history has been co-opted over the last 20+ years by confused greed and the vagaries of federal recognition. This protracted battle has splinted the tribe and yes, it has affected the Appalachian Trail.

I’ll spare you the recent sordid history of the Schaghticokes, but suffice it to say that it’s a huge mess.

I’ll spare you the recent sordid history of the Schaghticokes, but suffice it to say that it’s a huge mess.

The Schaghticoke consist of descendants of Mahican (also called “Mohican”, but not to be confused with the Mohegans), Potatuck (or Pootatuck), Weantinock, Tunxis, Podunk, and other people indigenous to what is now Connecticut, New York, and Massachusetts, who amalgamated after encroachment of white settlers on their ancestral lands. Their 400 acre reservation is located on the New York/Connecticut border within the boundaries of Kent running parallel with the Housatonic River.

One of the oldest reservations in North America, reserve land was granted to the Schaghticoke in the year 1736 by the General Assembly of the Colony of Connecticut, 40 years prior to the formation of the United States.

They have been fighting for federal BIA recognition for forever and that fight has split the tribe into  two camps who apparently hate each other. In fact, there was an act of arson on the reservation just this year which resulted in the destruction of the one permanent communal building on the land. Like I said, you can look all that up.

two camps who apparently hate each other. In fact, there was an act of arson on the reservation just this year which resulted in the destruction of the one permanent communal building on the land. Like I said, you can look all that up.

The AT ascends Schaghticoke Mountain, taking in the first excellent viewpoint (just barely still in CT) along the way. It exits Connecticut for a little over a mile – I’m not sure if this route is to take in the summit and a couple nice western views or to pretty much avoid the tribal land.

The competing groups are the Schaghticoke Tribal Nation led by the self-appointed chief Richard L. Velky and the Schaghticoke Indian Tribe which calls the former a “splinter group.” It’s nuts, especially as it involves only a handful of people.

Mile 6.1

My hike up the mountain was warm and sunny. But once I crossed the ridgeline and was in NY, the sky was grayer and the temperature dropped about 15 degrees with a biting wind from the west. It was almost biblical in nature. I was cold and really just wanted to cross back over the ridge into Connecticut and out of the wind.

Here, in NY, there is the NY summit of Schaghticoke Mountain, which (aha!) is not as high at the CT summit of the same mountain in a few miles. (Actually, it’s not really the same mountain but it is a different mountain of the same name. I think. Neither the CFPA map nor the AT map I have prints the name of the second, later peak, but the CFPA trail description does.)

There is another little marker denoting this re-entry into Connecticut, but there is nothing noting another little geographic tidbit that begins here as well. For the next 1/3 of a mile or so, down to a stream and up an over a rather steep hump to Indian Rocks Viewpoint, the trail is located on Indian reservation land.

This is the only stretch of the AT that traverses reservation land!

Now, I have read this fact on several different sites but I still find it sort of hard to believe. I have no idea, really, and don’t feel like putting in the effort to sort it out, so I’ll report simply what I read on the Internet. That never fails.

Mile 7.7

Back in 2000, the Schaghticoke nation protested the federal government’s denial of recognition by closing the portion of the AT that crosses their land for the entire July 4th weekend. This got them some press and I seem to recall a bit of scuttlebutt that they may force the trail off their land entirely. Looking at the map, I don’t really see why this is an issue as the trail could be moved a few hundred yards north to avoid their land, but I think the Indian Rocks viewpoint is on their land – and it’s a really rugged, really nice spot.

It’s also where you’ll notice my pictures change from late fall to late spring.

It’s also where you’ll notice my pictures change from late fall to late spring.

On my cold hike, I only saw a couple other day hikers all day and night. On my spring hike, I saw at least 20 other hikers – several of which I chatted with. After traversing Rattlesnake Den – a boulder-strewn hemlock gorge and passing a few more viewpoints of the Housatonic valley, I ran into a couple women inquiring about how best to return to their car later.

I offered them a ride, assuming we’d get back to my car spot around the same time. I also talked for a long time to a ridge-runner former two time thru-hiker on the unnamed/possibly named Schaghticoke Mountain. I really liked the idea of a somewhat lazy hike chatting it up with people who love the trail as much as I do.

I noticed about four beautiful pink lady’s slippers along this section as well. While not necessarily uncommon, they are fairly endangered and despite their beauty, they are easy to miss. I meant to ask the two women if they noticed them on their hike, but forgot. Here’s more on this fascinating plant from this site:

I noticed about four beautiful pink lady’s slippers along this section as well. While not necessarily uncommon, they are fairly endangered and despite their beauty, they are easy to miss. I meant to ask the two women if they noticed them on their hike, but forgot. Here’s more on this fascinating plant from this site:

Pink Lady’s Slipper is an interesting wildflower in the Orchid Family. They are endangered in some areas because they take a long time to grow, and because people collect them.

This plant has only two leaves. They are green and branch out from the center of the plant. A single flower stalk also grows from the center. The deep pink flower, which many people say looks like a slipper, grows about three inches long. Unlike most flowers you see, this flower is closed tightly except for a small opening in the front.

Pink Lady’s Slippers grow in shady forests under pine trees, oaks, Red Maple, and Sweetgum. In order to spread and grow new plants, Pink Lady’s Slipper needs help from other organisms. First, when a new seed is ready to grow, it must have a fungus help it. The fungus has not been identified by scientists yet, but we know it is in the Rhizoctonia Genus. The lady’s slipper seed does not have a food supply inside it, like most seeds do. It needs the threads of the fungus to break open the seed and attach themselves to it. The fungus will pass on food and nutrients to the Pink Lady’s Slipper seed.

Pink Lady’s Slippers grow in shady forests under pine trees, oaks, Red Maple, and Sweetgum. In order to spread and grow new plants, Pink Lady’s Slipper needs help from other organisms. First, when a new seed is ready to grow, it must have a fungus help it. The fungus has not been identified by scientists yet, but we know it is in the Rhizoctonia Genus. The lady’s slipper seed does not have a food supply inside it, like most seeds do. It needs the threads of the fungus to break open the seed and attach themselves to it. The fungus will pass on food and nutrients to the Pink Lady’s Slipper seed.

The seed will grow very slowly into a new plant. Without the fungus helping it, the plant could not grow. The plant will return the favor to the fungus when it is older. The fungus can soak up nutrients from the lady’s slipper that it could not get by itself. Pink Lady’s Slippers can live to be twenty years old or more.

This wildflower also needs help from bees. Its closed flower means that only a strong insect, like a bumble bee can push its way inside. The flower smells sweet, so the bee is tricked into thinking it holds nectar. When the bee gets inside it not only finds no nectar, but it realizes it is trapped. It cannot get back out the way it got in. The bumble bee explores and find a new way to squeeze out of the flower. To do so, it must push past a part of the flower called a stamen. The bee gets out, but it also gets covered with pollen that was on the stamen.

If the bumble bee gets tricked again by another Pink Lady’s Slipper, it will deliver pollen from the first flower, and get covered with pollen again by the new flower. The bee may do this several times before it figures out to avoid Pink Lady’s Slipper. The bumble bee gets nothing out of the relationship. Without the bee’s help, the plant could not make new seeds.

Nature is an amazing thing, isn’t it? Knowing all this about this beautiful humble little survivor, give it a careful little flower high-five next time you see one out in the woods. And if you think it’s about to get trampled, you can learn all about how to transplant one here. (pdf)

……………………………………………………………………………………………….

9.4 Miles

At the summit of the CT Schaghticoke Mountain, there are some great seasonal views. The area is populated by beech trees and some grassy matting all over the ground around the large exposed rock faces. It’s just a beautiful area that I really enjoyed on a perfect day.

At the summit of the CT Schaghticoke Mountain, there are some great seasonal views. The area is populated by beech trees and some grassy matting all over the ground around the large exposed rock faces. It’s just a beautiful area that I really enjoyed on a perfect day.

A steep decent down into a ravine and the pretty Thayer Brook was the precursor to a fairly steep ascent of Mt Algo. (My page on the Thayer Brook Cascades is here.) South to north, the ascent isn’t too bad at all. But I can report that coming the other way from route 341 is a bit tougher. You ascend 800 feet in less than a mile. The trail used to ascend/descend the Grand Staircase which, by all accounts, was pretty awful.

Now it’s really not so bad at all. I made a detour on my way down to 341 to stop in at the Mt Algo shelter which is right next to a rather loud brook. I spoke with some section hikers (both had started a week prior and both were going to about the MA/VT border.)

I had to leave them for a while and shuttle the two aforementioned women back to Bulls Bridge. I promised to pick up some beer and food to treat them as well.

On my way down Mt. Algo to the car I came across a giant millipede. These guys are fairly common in Connecticut but usually stay underneath the leaf litter. I made friends with him – which is a good thing. Because Narceus americanus, when threatened, sometimes release a noxious liquid that contains large amounts of benzoquinones which can cause dermatological burns. This fluid may irritate eyes or skin. (And just so you know, many other millipedes secrete hydrogen cyanide, and while there have also been claims that N. americanus releases hydrogen cyanide, this is not true.)

They do however, plop out the substance that causes a temporary, non-harmful discoloration of the skin.

Anyway, I drove the women and ended up making friends with the two women who work for chic-chic hotels in NYC and Washington DC. I bought them overpriced iced mochas at Belgique (part of the CT Chocolate Trail – my visit) before I knew this about them and was quite happy to learn of their rather excellent professions. They’ll read this so hello to Claudia and Pam and I look forward to staying in your fine establishments and say hello to Chef Art Smith for me. I puttered around town for a while, and picked up some beer and stuff for the guys back at the shelter and spent a great night there.

……………………………………………………………………………………………….

Mile 11.5

The trail crosses route 341 where there is a very large hiker lot on the side of the road. After crossing a stile – the only one in Connecticut I think – and a floodplain with a garter snake infested bridge, it was back to climbing up another little mountain called Fuller Mountain. But since I agreed with myself to separate my AT pages per CFPA Walkbook sections (which make sense regarding the shelters for average hikers), I shall do so.

At my old job working with insurance, we received a note from a guy working with a private military contractor cleaning the remote island up of all its radioactive and chemical agent waste. He was questioning some insurance issues related to having his leg bitten off by a shark.

[on telephone]

“We are sorry, Mr. Jones, but you suffered your injury while engaged in hazardous activities as prohibited by your policy. See Clause D, section 1, subsection (c), entitled “Prohibited Activities – hazardous waste cleanup.”

“But you don’t understand, a shark bit my leg off!”

“Once again, I refer you to Clause D, section 1, subsection (c). Thank you for doing business with XYZ Insurance and have a nice day.”

Comment #1 on 06.17.12 at 12:26 am